Powered by WPeMatico

Trusaiche blogaichean

Powered by WPeMatico

Tha mi gu math dèidheil air an Island Line

Sin an rathad-iarainn ann an Eilean Wight ann an Sasainn. Tha an loidhne (Ryde Pier Head-Shanklin) na pàirt den lìonra nàiseanta ach chan eil i idir ceangailte ri tìr mòr.⠀

Tha an loidhne na nàdar de Mhecca airson daoine aig a bheil ùidh ann an trèanaichean.

Carson?

Tha seirbheisean rèile an eilein air an ruith le seann thrèanaichean tiùb bho Underground Lunnainn.

Chaidh an loidhne a dhealanachadh ann an 1967 ach a chionn ’s gu bheil tunail gu math ìosail ann an Ryde, cha ghabhadh trèanaichean àbhaisteach a chleachdadh.

Gu tòiseach na bliadhna seo, bha an loidhne ga ruith le trèanaichean tiùb a thogadh 80 bliadhna air ais – “stoc 1938”. Bhiodh daoine a’ dol ann bho air feadh an t-saoghail gus am faicinn.

Chaidh mi fhèin ann gus na trèanaichean fhaicinn air ais ann an 2013. Bha mi an dùil aig an àm nach biodh na trèanaichean ann fada. Bha e follaiseach aig an àm gun robh an dà chuid trèanaichean agus bun-structar na loidhne feumach air ath-nuadhachadh ann an ùine nach biodh fada.

Gu dearbha, bha teagamh ann aig deireadh nan 2010an am maireadh an loidhne idir mar thoradh air an t-suidheachadh seo. Bha an riaghaltas a’ beachdachadh air an loidhne a thoirt a-mach às an lìonra nàiseanta agus a thoirt do dh’urras coimhearsnachd ach bha a’ choimhearsnachd fhèin den bheachd nach biodh sin seasmhach a chionn ’s nach robh dòigh sam bith aca gus an t-airgead a thogail airson trèanaichean ùra is obair ath-nuadhachaidh.

Bhathar cuideachd a’ beachdachadh air tramaichean a chur an àite nan trèanaichean.

Aig a’ cheann-thall, ge-tà, cho-dhùin an riaghaltas gum bu chòir an rathad-iarainn a chumail fosgailte, a sgeadachadh agus trèanaichean ùra fhaighinn – an co-dhùnadh ceart nam bheachd.

Air an adbhar seo, ruith na seann thrèanaichean tiùb airson an turais mu dheireadh air 3 Faoilleach 2021 agus dhùin an loidhne. Gu mì-fhortanach, cha robh cothrom ann gus an suidheachadh seo a chomharrachadh mar bu chòir mar thoradh air a’ Chòrnonabhìoras.

Tha trèanaichean ùra air tighinn dhan eilean agus tha obair sgeadachaidh a’ dol air adhart. Fosglaidh an loidhne as ùr aig tòiseach a’ Ghiblein.

⠀

Bu chòir dhomh a ràdh nach eil na trèanaichean “ùra” buileach ùr, tha iad ath-chuairtichte – no suas-chuairtichte (up-cycled) bho Underground Lunnainn cuideachd – D-stock bho Loidhne an District ach chaidh an sgeadachadh chun na h-ìre is nach eil mòran air fhàgail den t-seann trèana agus tha iad tòrr na spaideile na bha iad riamh roimhe.⠀

Agus tha na trèanaichean seo nas motha na na trèanaichean a bh’ ann roimhe – ach fhathast comasach air a dhol tron tunail ann an Ryde!

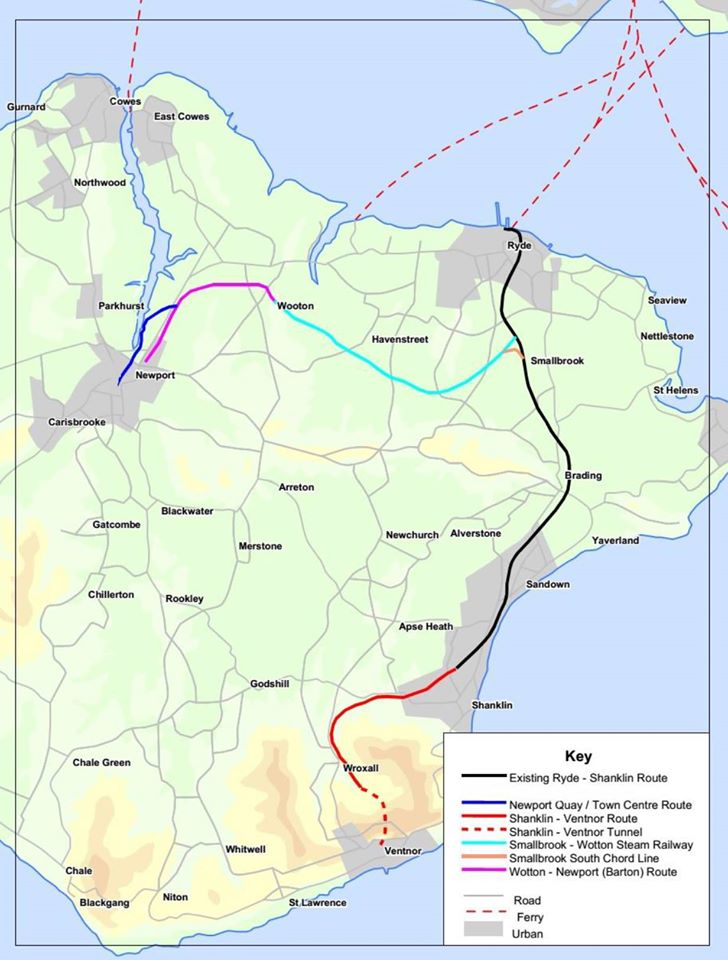

A bharrachd air na trèanaichean ùra, dh’fhaodte gum faigh an t-eilean rathaidean-iarainn ùra cuideachd – tha Riaghaltas na RA air pàigheadh gus sgrùdaidhean comais a dhèanamh mu bhith a’ leudachadh na loidhne a th’ ann mar-thà gu Ventnor agus mu bhith ag ath-fhosgladh na loidhne gu Newport (Casnewydd!!??) , prìomh bhaile an eilein.

Seo mapa:

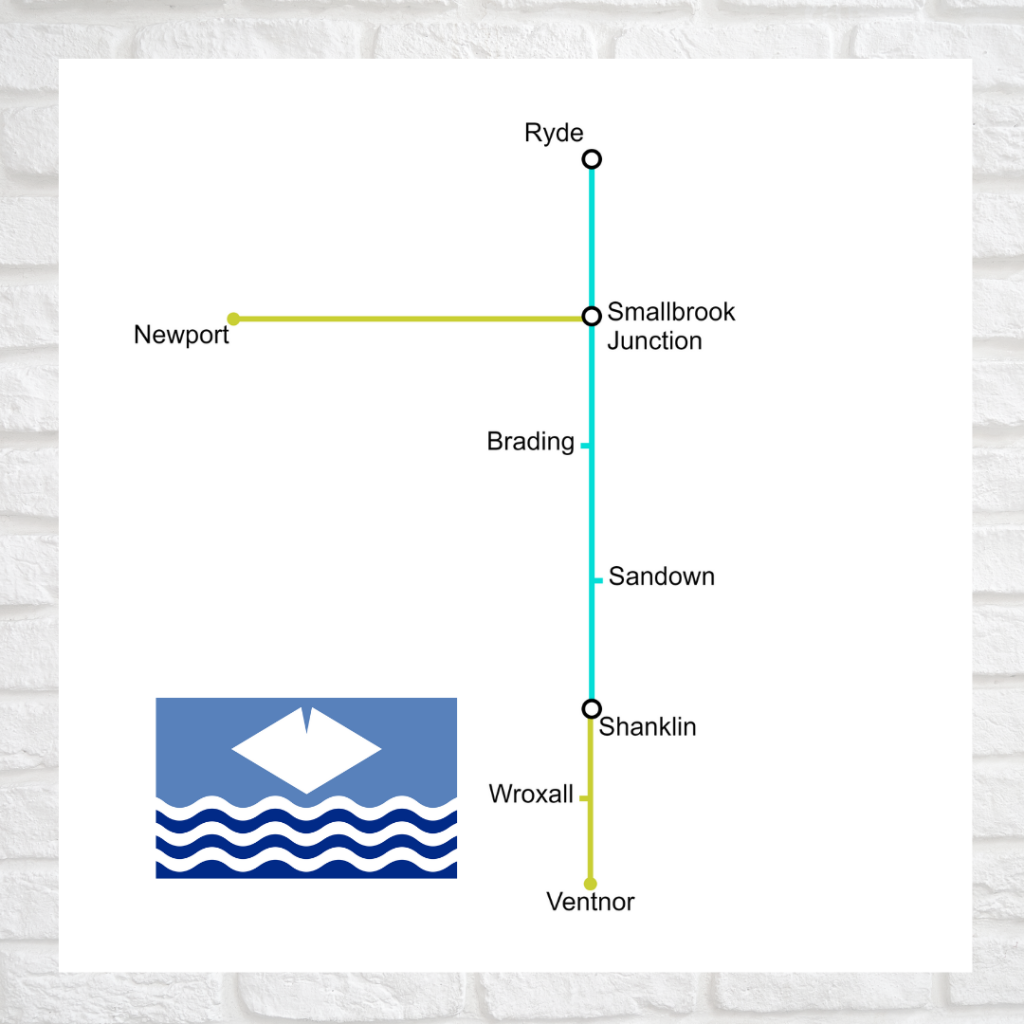

Agus seo mapa nas sìmplidhe a rinn mi fhèin. Tha na loidhnichean a th’ ann mar-thà ann an cyan agus tha loidhnichean a dh’fhaodadh a bhith ann san àm ri teachd ann an uaine.

Tha mi an dùil is an dòchas gum faigh mi cothrom a dhol ann gus na trèanaichean ùra nuair a bhios zombie apocolypse a’ Chorònabhìorais deiseil!

Alasdair

Tadhail air Trèanaichean, tramaichean is tràilidhean

Powered by WPeMatico

Tadhail air Ghetto na Gàidhlig – Bella Caledonia

Powered by WPeMatico

Le lasairdhubh

Tha seo ro mhath! Le Eoin P. Ó Murchú còir.

Tadhail air Air Cuan Dubh Drilseach

Powered by WPeMatico

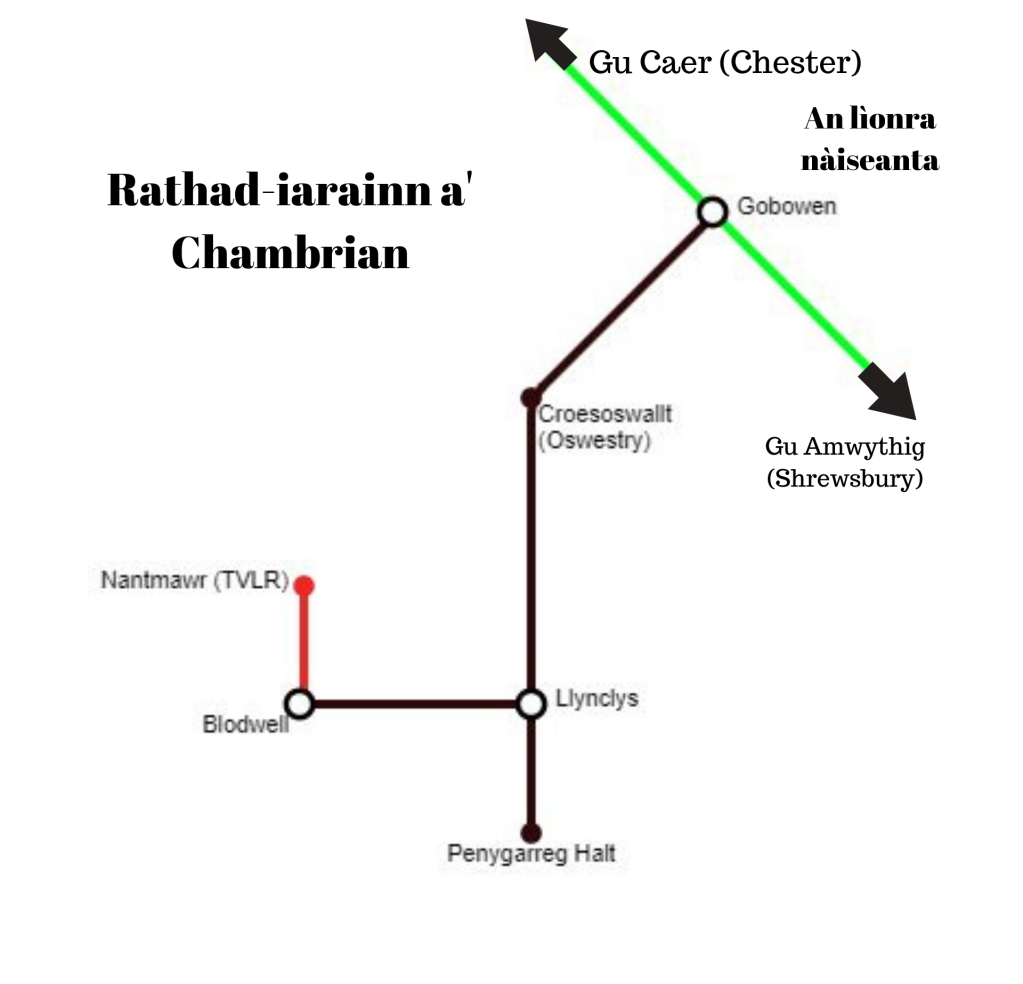

Chaidh mi gu rathad-iarainn beag snog air a’ chrìch eadar Sasainn is a’ Chuimrigh an-ùiridh. ‘S e an Tanat Valley Light Railway an t-ainm a th’ air. ⠀

⠀

Ged a tha e ann an Shropshire, Sasainn, tha na h-ainmean-àite san sgìre sa Chuimris – Nantmawr is Blodwell is eile.⠀

⠀

Air a’ mhapa, tha an loidhne uaine na pàirt den lìonra nàiseanta. Tha na loidhnichean dubha a’ riochdachadh nam planaichean leudachaidh aig loidhnichean glèidhte: The Cambrian Railway (Oswestry agus Llynclys) agus an Tanat Valley Light Railway. Tha trì loidhnichean beaga fa leth ann aig an àm seo – ann an Nantmawr, Oswestry agus Llynclys ach seo am plana aca san ùine fhada. ⠀

⠀

Tha an Tanat Valley Light Railway air iomairt a thoiseachadh gus airgead a thogail gus òrdugh fhaighinn fo Achd Còmhdhail is Obraichean (Transport and Works Act order) fhaighinn gus am bi cead aca trèanaichean a ruith air an loidhe aca air fad.⠀

⠀

Feumaidh iad £100,000 uile gu lèir airson seo. Ma tha thu airson not no dhà a thoirt dhaibh – mar a thug mi fhèin – faodar sin a dhèanamh air an làraich-lìn aca.

Alasdair

Tadhail air Trèanaichean, tramaichean is tràilidhean

Powered by WPeMatico

Le lasairdhubh

It is vitally important that we build a Gaelic-revival movement that is as inclusive and open as possible. Both tactically and ethically, a revival that excluded any speakers would be a dead end. But to open up the revival to everyone, we first need to redefine the central Gaelic identity, the Gael, to include everyone who speaks the language, regardless of race, ancestry, religion, sexual orientation, place of residence, or anything else.

While this path forward is progressive, and precedented in other language-revival movements (e.g. Urla 1988), it is not surprising perhaps that some voices have been raised against the idea. In the course of these counter-arguments, critics have sometimes made their own normative statements about who is a real Gael, voicing, as it were, their understanding of what is ‘common sense’ or what ‘the community’ really believes.

But how do they know? When folk hold forth on this issue, speaking either as non-Gaels or as Gaels themselves, and making broad statements about who is inside and outside of the group, how do they really know what other Gaelic speakers actually think? As humans, we are pretty poor at estimating the opinions of others, and we tend to see our own views as more average or normal than they actually are. (Kitts 2003, Mullen et al. 1985) Is there really any consensus out there about the identity of a real Gael, and if there is, how would we know?

As it turns out, Gaelic identity is a fairly well-studied question in sociolinguistics and linguistic anthropology in Scotland. We now have some excellent data on how different groups understand their identity as Gaelic speakers. In this post, I would like to review some of these data and consider what they can tell us about the real state of Gaelic identity in Scotland, and show, unequivocally I think, that the situation is very complex, and that we do not presently have anything like a consensus on this question, in traditional Gaelic communities or anywhere else.

Some of the best recent data on Gaelic identity in traditional Gaelic-speaking communities were collected by a pair of researchers from the University of Edinburgh, the late Frank Bechhofer and his research partner David McCrone. As they explained it, they sought to identify those attributes that folk in traditional Gaelic communities consider essential in order to be recognized as a Gael:

So what makes a Gael? Is it a matter of language: if you speak Gaelic, you are a Gael; and if not, [why] not? So, if you are an incomer to the Gàidhealtachd and you become fluent in Gaelic, do people accept you as a Gael? Or is that insufficient? Does someone need to have ancestral roots – traceable through their family? And can you be a Gael if you do not live in the Gàidhealtachd? If speaking Gaelic is not all-important, how do these markers – speaking Gaelic, living in the Gàidhealtachd, and having Gaelic ancestry – stack up against each other? Does having the language trump residence and/or ancestry? Would you be taken for a Gael if you have ancestry, but neither residence nor language?

Bechhofer and David McCrone 2014: 127

Bechhofer and McCrone asked a sample of folk living in Gaelic-speaking areas, people who themselves strongly identified as Gaels, if they would accept a range of different kinds people as fellow Gaels, and this is what they found:

80% of these Gaels would accept someone else as a fellow Gael if that person had Gaelic ancestry, could speak Gaelic, but did not live in the Gàidhealtachd.

64% would accept someone as a fellow Gael if that person lived in the Gàidhealtachd and had Gaelic ancestry, but did not themselves speak Gaelic.

58% would accept someone as a fellow Gael if that person spoke Gaelic and was born in Scotland, but did not have Gaelic ancestry.

29% would accept anyone with Gaelic ancestry as a fellow Gael.

28% would accept any Gaelic speaker as a fellow Gael, even if they were not born in Scotland.

As we can see, several markers of identity appear to be important, but not to the same degree by all people, or in the same combination. Some folk were fairly restrictive, requiring a combination of markers including place of residence, ancestry and Gaelic ability, while a significant minority were open to extending membership based on ancestry or Gaelic ability alone.

From these data, it appears that a clear majority (58%) would be willing to consider someone without Gaelic ancestry as a fellow Gael, as long as that person was born in Scotland and could also speak Gaelic, for instance, a Scottish child of African or Asian decent attending GME in Edinburgh or Glasgow. And it also appears that a significant minority of Gaels in this group (28%) would even be willing to consider a new speaker of Gaelic from Seattle like myself as a fellow Gael.

We can imply from these data that those who would take the most restrictive definition of a Gael (i.e. someone of Gaelic ancestry, with Gaelic acquired in the home and living in a Gaelic-speaking area) would be very much in the minority amongst those Gaels actually living in these areas. Based on these data, Bechhofer and McCrone concluded that, “Gaelic identity should be considered as open and fluid, rather than fixed and given.” (2014: 127)

Others have asked some of the same questions, but of learners or new speakers, rather than speakers from traditional communities, and the results are interesting. Some of the most comprehensive research on Gaelic learners in Scotland was conducted about twenty years ago by Alasdair MacCaluim for his PhD thesis. Alasdair asked learners in his survey if they considered themselves Gaels, and surprisingly, while only 23.8% of beginner learners considered themselves Gaels, as many as 56.1% of fluent learners did. (MacCaluim 2002: 180) Also interestingly, only 6.6% of the learners in his survey would define a Gael as anyone who speaks Gaelic, (MacCaluim 2006: 195), ironically, significantly lower than the number of Gaels living in Gaelic-speaking areas who would do the same.

More recently (2014), Wilson McLeod, Bernadette O’Rourke and Stuart Dunmore published a report of interviews and focus-group sessions with 35 new speakers from Glasgow and Edinburgh and found that, “most of the participants […] did not feel themselves to be Gaels.” (21) These data were collected from interviews, while MacCaluim’s data above were collected in a survey, from a somewhat different group, and also, more than a decade earlier, so it is difficult to compare these results directly, but it is fair to say that there appears to be no more of a consensus about Gaelic identity amongst learners and new-speakers as there is amongst people living in traditional communities.

There is a particular subset of Gaelic speakers that is especially important to the future of the language, and they are students in GME. In 2005, James Oliver published results of interviews with high school students in Glasgow and Skye, looking at the differences in identity between students in the GME stream and the EME stream, and he found that, at this stage in their education, most GME students identified as Gaels, while learners and non-Gaelic speakers generally did not:

| Are you a Gael | Fluent Speakers | Learners | No Gaelic | Total |

| Yes | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Maybe | 7 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| No | 3 | 12 | 11 | 26 |

| Total | 21 | 12 | 12 | 43 |

This shows fairly strong support for Gaelic identity amongst GME students, but more recent research amongst former GME students shows far less support. Stuart Dunmore interviewed 130 adults who entered GME between 1985 and 1995, and he found that only a minority of these graduates still used Gaelic daily, and that very few identified as Gaels:

[…] the majority of Gaelic medium-educated adults’ identification as Gaels was either weak, or rejected out of hand. […] if immersion pupils do not develop social identifications and supportive ideologies toward the languages through which they are educated, it should not necessarily be surprising if they do not then speak the language outside of the classroom, or after completing formal education.

Dunmore 2017: 737

Here Dunmore also proposes that their may be a direct causal link between former GME students’ weak identification with Gaelic on the one hand and their low reported use of the language in their daily lives on the other.

Heretofore, we have been considering Gaelic identity in Scotland, but of course, Gaelic isn’t only spoken here. Dunmore has also recently published results from research conducted on new speakers of Gaelic in Nova Scotia, and he found that Canadian new speakers are markedly more likely to see themselves as Gaels (and proudly so, apparently) than their Scottish counterparts:

Whilst such a clear rejection of a social identity as Gaels is by no means uniformly expressed by all members of this group, the ethnolinguistic category is overwhelmingly avoided or problematized by most Scottish new speakers in my research. By contrast, Nova Scotian new speakers’ Gaelic identities are frequently expressed in enthusiastic terms, and it is clear that most new speakers in Nova Scotia embrace the Gael(ic) label when describing their identification with the language and motivations for having learned it.

Dunmore 2020: 12

There is much more research on this subject. Other researchers have conducted quite a bit of qualitative research on this question, but the data above represent some of the best quantitative and quasi-quantitative research to date, and they give a clear picture of the diversity of Gaelic identities in Scotland (and Canada). We definitely do not have a consensus on what is a Gael is anywhere, among any group of speakers, and therefore, I believe that going forward, as we work on the issue of Gaelic identity in our revival movement, it is critical that we build on the most open, inclusive conceptions of Gaelic identity and create a movement that is as broad as possible.

There will be plenty of very active Gaelic speakers who will have no interest in identifying as Gaels, and that is cool too. Everyone should be welcome, but that central identity has to be open to all, or we risk creating a two-tier revival where some speakers are considered more legitimate or valuable than others.

If we insist, as some would, on defining the core Gaelic identity, the Gael, very narrowly, based on some combination of ancestry, place of residence and language, we would exclude most Gaelic speakers in the process. We would exclude most of the young, fluent Gaelic speakers on my course at SMO, for instance. We would also exclude the nearly half of all Gaelic speakers who do not live in the Gàidhealtachd. And we would exclude most students in GME. It should be clear that this would be neither sustainable nor ethical.

But if we create a Gaelic identity that is open to all, it diminishes nobody. Loads of proud young Gaels in Canada, for instance, don’t diminish Gaels in Scotland in any way, and by the same token, proud young Gaels in Edinburgh or Glasgow won’t diminish Gaels in Lochboisdale, in Staffin, in Shawbost or anywhere else. It is not a zero-sum game. Nobody has to lose. The whole notion of language ownership is regressive and counterproductive in a Gaelic context. Gaelic is big enough for everyone, and the more speakers that we can welcome into our movement, the stronger and more vital the language revival will be.

I am super lucky to work at Sabhal Mòr Ostaig. The College is a lively and diverse microcosm of the whole Gaelic world. Gaelic speakers come from all over Scotland, and indeed from all around the planet, to work and study here. There are folk here like me, new speakers with no previous connection to Gaelic who are drawn to the College purely out of a love for the language. And there are native speakers from traditional communities who have selflessly dedicated their lives to passing on their language and culture to the next generation. But there are also plenty of folk who don’t fit neatly into either of those two groups.

There are students and staff who have grown up in Gaelic-speaking families, but outside of traditional Gaelic communities: in the East, in the Lowlands, and the cities of Scotland. There are those who were raised in Gaelic but by parents who learned the language as adults. There are those who grew up around Gaelic, and perhaps even spoke some of the language as children, but who did not acquire full proficiency, and who come to the College to learn or relearn the language as adults. There are white, Black and Asian students. There are native Scots, immigrants and foreigners. And of course, there are many students now, of all backgrounds, who acquired some or all of their Gaelic in GME rather than in the home.

And preconceptions notwithstanding, diversity in the Gaelic world is nothing new; Gaelic has always been a broad church. Historically, Gaels have been crofters and fishermen; peasants, clergy and kings; pirates and decedents of Vikings; Lowlanders and Highlanders; Scots, Manx, Irish and Canadians; Catholics, Protestants and Existentialists; scholars, poets and mercenary solderers; Jacobites and Hanoverians; Tories, Communists, Nationalists and Socialists, and much else. The one thing, perhaps the only thing, that all these different Gaels shared was the Gaelic language itself.

It is in this very diversity that we will now find a way forward for Gaelic. If we can embrace all Gaelic speakers as fellow Gaels, we will have the best chance of building the sort of revival movement that will guarantee a future for Gaelic as a spoken language in Scotland for generations to come.

Sources:

Bechhofer, Frank, and David McCrone (2014) “What makes a Gael? Identity, language and ancestry in the Scottish Gàidhealtachd.” Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power, 21(2): 113–133.

Dunmore, Stuart S. (2017). “Immersion education outcomes and the Gaelic community: identities and language ideologies among Gaelic medium-educated adults in Scotland.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 38(8): 726–741.

Dunmore, Stuart. (2020). “Emic and essentialist perspectives on Gaelic heritage: New speakers, language policy, and cultural identity in Nova Scotia and Scotland.” Language in Society, 1–23.

Kitts, James A. (2003) “Egocentric bias or information management? Selective disclosure and the social roots of norm misperception.” Social Psychology Quarterly, 66(3): 222-237.

MacCaluim, Alasdair (2002) Periphery of the periphery? Adult Learners of Scottish Gaelic and Reversal of Language Shift. Tràchdas PhD. Dùn Èideann: Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann.

MacCaluim, Alasdair. (2007). Reversing Language Shift: The Social Identity and Role of Adult Learners of Scottish Gaelic. Belfast: Cló Ollscoil na Banríona.

McLeod, Wilson, O’Rourke, Bernadette, and Dunmore, Stuart (2014) ‘New Speakers’ of Gaelic in Edinburgh and Glasgow. Soillse, [www.soillse.ac.uk accessed 1/6/2014].

Mullen, Brian, Jennifer L. Atkins, Debbie S. Champion, Cecelia Edwards, Dana Hardy, John E. Story, and Mary Vanderklok. (1985) “The false consensus effect: A meta-analysis of 115 hypothesis tests.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 21(3): 262-283.

Oliver, James (2005) “Scottish Gaelic Identities: Contexts and Contingencies.” Scottish Affairs 51.

Urla, Jacqueline. (1988) “Ethnic Protest and Social Planning: A Look at Basque Language Revival.” Cultural Anthropology, 3(4): 379–394.

Tadhail air Air Cuan Dubh Drilseach

Powered by WPeMatico

Le Steaphan

Powered by WPeMatico

Bidh an t-Oll. Wilson MacLeòid a’ tighinn a thadhail air a’ Chomann oidhche Dhiardaoin sa tighinn (10mh dhan Dùbhlachd). Is ann am Beurla a bhios an t-Oll. MacLeòid a’ bruidhinn air a’ cheann a chithear gu h-àrd. Tha sinn a’ dèanamh fiughar mhòir ri bhith cuir fàilte air Wilson agus tha sinn gu mòr an dòchas gun urrainn dhuibh a bhith cuide ruinn air-loidhne air Zoom.

| Àm: | 7.30f, Diardaoin 10ᵐʰ dhan Dùbhlachd |

| Àite: | Coinneamh tro mheadhan Zoom. Innsidh sinn a, facal-faire an-seo son choinneamh. |

| Cànan: | Beurla |

We are very much looking forward to welcoming Professor Wilson McLeod this Thursday evening and hope you can come and join us on Zoom. Professor McLeod’s talk will be in English on the topic outlined above. Hope to see you all there!

| When: | 7.30pm, Thursday 10th December |

| Where: | Via Zoom meeting. Password: we’ll add it before the meeting. |

| Language: | English |

Tadhail air Comann Gàidhlig Ghlaschu

Powered by WPeMatico

Le Gordon Wells

Μια ταινία μικρού μήκους για το κέντρο ημέρας Craigard στο Lochmaddy, στα Δυτικά Νησιά της Σκωτίας. Πρόκειται για ένα μέρος, όπου πολλά άτομα περνούν δημιουργικά και ευχάριστα το χρόνο τους.

Μια ταινία μικρού μήκους για το κέντρο ημέρας Craigard στο Lochmaddy, στα Δυτικά Νησιά της Σκωτίας. Πρόκειται για ένα μέρος, όπου πολλά άτομα περνούν δημιουργικά και ευχάριστα το χρόνο τους.

Originally made in 2006, our Craigard documentary is now re-published with a commentary in Greek, as part our “Other Tongues” initiative, in which our films are shared with other languages around the world. It’s a particular pleasure to see our first ever documentary, and still one of our favourites, brought back to life in this way!

As usual, a wordlinked Clilstore transcript – with the film embedded – is also available. You can find it here: https://multidict.net/cs/9062

Our narrator this time is Valentini Litsiou of C.V.T. Georgiki Anaptixi – an early partner with Sabhal Mòr Ostaig in one of the follow-up initiatives to the POOLS project out of which Island Voices/Guthan nan Eilean was born. So it seemed particularly appropriate to “go back to the beginning” when Valentini selected “Craigard” as the film she would like to translate and narrate.

Valentini still works for the same group, offering support in public relations, and has been involved in various other European projects. She’s always enjoyed this work because of the opportunities it’s offered to meet people of other cultures, who speak other languages, and who have other ways of thinking.

Valentini still works for the same group, offering support in public relations, and has been involved in various other European projects. She’s always enjoyed this work because of the opportunities it’s offered to meet people of other cultures, who speak other languages, and who have other ways of thinking.

She also has a wide range of domestic interests, but is not enjoying this period of COVID-19 restrictions. Luckily for us, it didn’t stop her from making this excellent new contribution to Island Voices in double quick time! Perhaps the earlier experience of POOLS-related recording work made it an easy decision for her to get involved again?

Or maybe she’s just a natural star – witness her contributions in “Mi piace questo binario!”, also recently dusted off and re-presented…

Tadhail air Island Voices – Guthan nan Eilean

Powered by WPeMatico