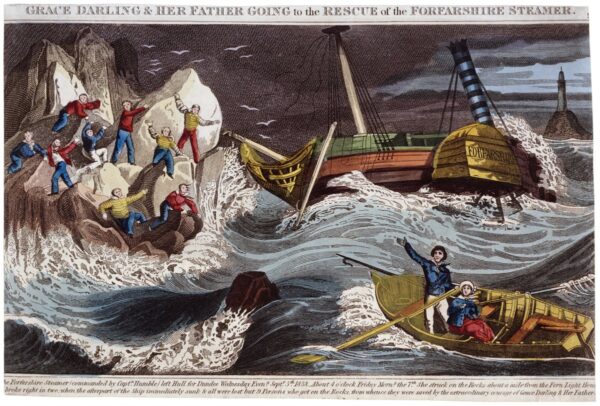

Bana-ghaisgeach nan cuantan, Grace Darling

O chionn 185 bliadhna air an 7 latha den t-Sultain shàbhail Grace Darling agus a h-athair naoinear às an long-bhriste HMS Forfarshire. Mar bhana-ghaisgeach na mara tha e iomchaidh gum bi cuimhne againn oirre nar coimhearsnachd chladaich air an ceann-là seo.

Rugadh Grace ann an 1815 ann an Northumberland, mar nighean neach-taigh-sholais, agus ann an 1838 bha Grace a’ fuireach còmla ris agus a màthair anns an taigh-solais Eilean Longstone, air fear de na h-Eileanan Farne. Bha Grace 22 aig an àm sin agus a’ cuideachadh le obair an taighe agus an taigh-sholais, nam measg le cumail faire.

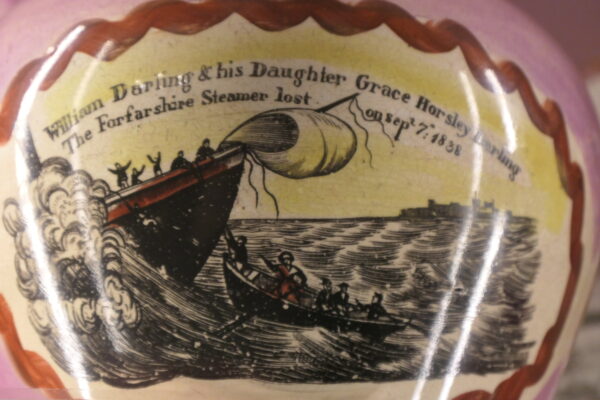

Sna h-uairean tràtha den 7 den t-Sultain, a bha gu sònraichte stoirmeil, chunnaic Grace briseadh-luing eagalach bho uinneag an t-seòmair-chadail aice – bhuail bàta-smùide eilean ìosal creagach, Big Harcar Rock, mu mhìle air falbh, agus bhris na dhà leth. Thachair sin mu 4 uairean sa mhadainn. Ruith i dhan phrosbaig feuch am faiceadh i duine beò sam bith, ach bha e fathast ro dhorcha, ach an ceann ùine dh’aithnich iad daoine air a chreig. Cho-dhùin Mgr Darling agus Grace gun iomraicheadh iad an sin, a dh’aindeoin staid uabhasach na sìde ‘s na mara, gus feuchainn ri na truaghanan a shàbhaladh. Bha fios aca gum biodh sin na bu luaithe na feitheamh air a’ bhàta-teasairginn à Seahouses (e fhèin bàta-ràmh), nach toisicheadh idir, ‘s dòcha, leis an t-sìde ‘s an astar na bu mhotha.

Às dèidh saothrach anabarraich, chaidh aca air an copal aca a stiùreadh dhan àite, far an deach Mgr Darling suas air a’ chreig a’ fàgail Grace na h-aonar a’ cumail am bàta faisg air làimh sa mhuir fhiadhaich ‘s san stoirm fheargach. Lorg iad naoinear luchd-teasairginn, cus rim toirt dhan taigh-sholais ann an aon bhaidse. Dh’iomair iad a’ chiad fheadhainn air ais – boireannach, fear air a ghoirteachadh, agus triùir den chriutha, agus an uair sin dh’iomair Mgr Darling agus an criutha air ais airson chàich. Dh’fhuirich Grace san taigh-sholais gus coimheadh às dèidh an fhir lèonta agus a’ bhoireannaich, a chaill dithis cloinne san tubaist. Ro 9 uair sa mhadainn bha a h-uile naoinear sàbhailte ann an Longstone.

Bha an HMS Forfarshire air an t-slighe bho Hull gu Dùn Dèagh le 62 daoine air bòrd. Bha na goileadairean air am fàilneachadh agus mar sin bha an t-einnsean gun fheum, agus cha robh aig a’ chaiptean ach nàdar de sheòl ri chleachdadh san stoirm. Shaoil e am mearachd gur e taigh-solais Inner Farne a bh’ anns an Longstone agus dhrioft am bàta-smùide air an eilean chreagach neo-fhaicsinneach. Bhrìs an long na dà leth, agus ron ghlasadh an latha cha mhòr nach robh e air a dhol fodha. Chaidh aig naoinear eile air teicheadh anns a’ bhata-teasairginn aig an long fhèin agus chaidh an sàbhaladh le long eile san dol seachad. Chaidh na cuirp-chloinne a lorg cuideachd leis a’ bhàta-teasairginn à Seahouses (is bràthair Grace air aon de na ràimh). B’ feudar dhan bhàta sin cuideachd feitheamh fad 3 làithean aig taigh-solais Longstone air sgàth na sìde.

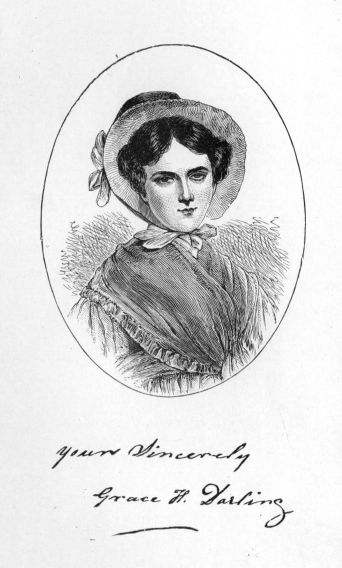

Nuair a nochd an naidheachd, chaidh Grace na bana-ghaisgeach chliùiteach air feadh na dùthcha. Fhuair i urraman, duaisean (nam measg £50 bho Bhanrìgh Bhictoria!), agus fiù ‘s tairgsean-pòsaidh. Chaidh bàrdachd is òrain a sgrìobhadh mu a deidhinn agus chaidh iomadh portraid a pheantadh. Gu mi-fhortamach ge-tà, cha robh mòran ùine air fhagail dhi gus tlachd a ghabhail na cliù (ma ghabh idir) – chaochail i leis a’ chaitheamh dìreach 4 bliadhna às dèidh sin. Thàinig na ceudan dhan tiodhlacadh ann am Bamburgh, far a bheil carragh-chuimhne brèagha san chladh aig eaglais eachdraidheil Naomh Aodhan, agus tha an iomhaigh-chloiche shnaithte àlainn a bha air an tuama aice air a gleidheadh am broinn na h-eaglais. Bha cothrom agam tadhal orra nuair a bha mi ann an Northumberland an-uiridh. Tha taigh-tasgaidh RNLI Grace Darling ann am Bamburgh cuideachd. https://rnli.org/find-my-nearest/museums/grace-darling-in-10-objects

Tha bana-ghaisgeach iomraidh againne ann am Machair Rois cuideachd – Oighrig an Dà Raimh; cuimhnichean, còmhla ri dìleab shònraichte Grace, gun do chluich na boireannaich cuideachd riamh am pàirt ann am dràma nan cuantan.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Maritime heroine, Grace Darling

On 7 September it will be 185 years since Grace Darling and her father saved the lives of nine souls from the wrecked HMS Forfarshire. As a maritime heroine, it’s fitting for our coastal community to remember her on this anniversary.

Grace was born in 1815 in Northumberland, daughter of a lighthouse-keeper, and in 1899 Grace and her mother were living with him in Longstone Island lighthouse, one on of the Farne Islands. Grace was 22 then, and helping with household and lighthouse duties, including taking turns at watch.

In the exceptionally stormy night to 7 September Grace saw from her bedroom window a terrible wreck happening – a steamship hit a low rocky island, Big Harcar Rock, about a mile away, and broke in two. This happened about 4am. She ran to the lighthouse telescope to see if she could spot survivors but it was still too dark, but eventually they could make out some people on the rock. Mr Darling and Grace decided to row there, despite the dreadful conditions, and try to rescue them – they knew that would be quicker than waiting for the lifeboat (also a rowing boat) from more distant Seahouses, which might not even have launched due to the weather conditions and distance.

With immense effort, the two of them managed to get their coble to the scene, Grace on her own holding the boat steady in the raging waters and storm while her father went onto the rock. They discovered nine survivors, too many for one trip back to the lighthouse. They brought back the first batch, a woman, an injured man, and three crewmen to Longstone, and then Mr Darling and the crewmen rowed back to get the remaining survivors while Grace and her mother tended the injured man and the woman, whose two children had been lost. By 9am all nine were safely at the lighthouse.

The ship was the HMS Forfarshire, en route from Hull to Dundee with 62 people on board. The ship’s boilers had failed, so the engine was useless, and the captain only had a makeshift sail to use in the storm. He mistook the Longstone light for the Inner Farne one, and drifted onto the unseen rocky island. The ship broke in two, and by morning was almost completely sunk. Nine other people had managed to board the ship’s lifeboat and were later picked up by a passing ship – all others were lost. The two drowned children’s bodies were also picked up later by the Seahouses lifeboat (with Grace’s brother on one of the oars). That lifeboat also had to shelter at the lighthouse for 3 days because of the weather.

Once the news broke, Grace was celebrated as a heroine throughout the land. She received honours, rewards (including £50 from Queen Victoria!), and even proposals of marriage. Poems and songs were written about her and her portrait was freqently painted. Sadly, however, she didn’t live long to enjoy the admiration (if indeed she did) – she died of tuberculosis only four years later. Crowds turned out for her funeral in Bamburgh, where she has an ornate monument in the churchyard of historic St Aidan’s Church, and the beautiful recumbent carving from her tomb is now preserved inside the church. I was able to visit them while in Northumberland last year. There is also a RNLI Grace Darling Museum in Bamburgh : https://rnli.org/find-my-nearest/museums/grace-darling-in-10-objects

On the Seaboard we also have our rowing heroine – Effie of the Two Oars; a reminder, along with Grace’s remarkable legacy, that women too have always played their part in the drama of the seas.

-

CC -

-

CC

Tadhail air seaboardgàidhlig

Powered by WPeMatico

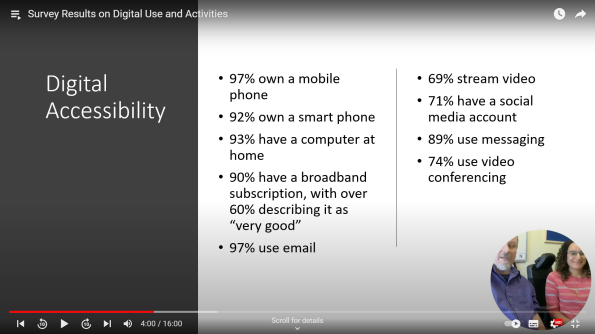

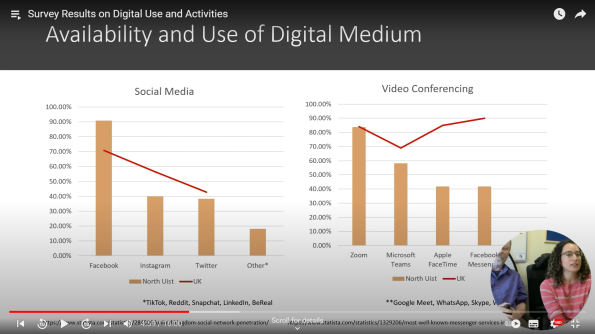

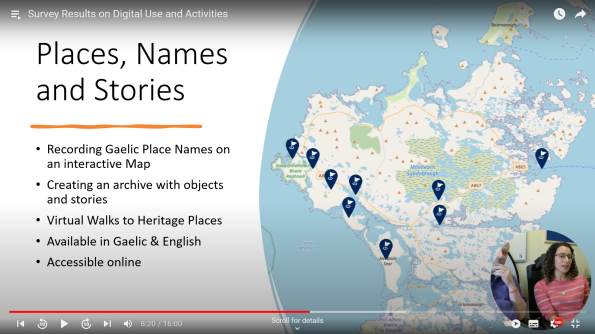

The second Digital Fèis for Aire air Sunnd is now scheduled for 11th and 12th August, taking the place of the May event which had to be postponed. Here’s the updated

The second Digital Fèis for Aire air Sunnd is now scheduled for 11th and 12th August, taking the place of the May event which had to be postponed. Here’s the updated