Le Rody Gorman

Powered by WPeMatico

Tadhail air Gormanaich

Trusaiche blogaichean

Le Rody Gorman

Powered by WPeMatico

Tadhail air Gormanaich

Le Gordon Wells

Tommy Macdonald tells some of the history of Clann ‘ic Mhuirich (“Clan Currie”) from the ruin of the ancestral home in Stilligarry, South Uist, and recounts some tales from other nearby sites.

In Part 1, he relates where Clann ‘ic Mhuirich came from, and when, and how they came to settle in Uist eventually. Their hereditary bardic role spanned centuries of Scottish history, before petering out with the loss of patronage, of skills, and eventually of manuscripts.

In Part 2, Tommy explains how Stilligary came to be known as “Baile nam Bàrd”. He goes on to talk about changes of the Mac Mhuirich family name. The impressive size of the ruin and some archaeological finds point to their importance in the community, and the power the family could exercise through their poetic and scholarly skills. He finishes with a short recitation.

In Tobhta Fhearchair, Tommy goes on to tell some of the history of the Beatons from the ruin of Fearchar’s home on the boundary between Tobha Mòr and Dreumasdal. He explains that the Beatons were renowned as doctors, especially in the West of Scotland, with strong connections to Skye and Islay as well as Uist. He refers to the work of Alasdair Carmichael (Carmina Gadelica) to illustrate their knowledge of plants and their uses, while acknowledging that Fearchar himself may not have been as knowledgeable as his forebears. A finishing quote from Martin Martin underlines the family’s historical association with the medical profession.

At Dùn Raghnaill, built for Clanranald, Tommy relates the story of why it was built – to protect the clan chief Mac ‘ic Ailein from his own family – in a time of sometimes bloody sea-borne raids along the Minch. According to local history, it was later used to imprison a daring sea-faring Mac Mhuirich, whose hereditary bardic skills were such that the style of his composition from within the prison walls of the song “Mulaid Prìosanach ann an Dùn Raghnaill” was sufficient for him to be recognised and identified by his own estranged father.

All four films – with optional subtitling available for learners or non-speakers of Gaelic – have been added to the taighean-tughaidh playlist. This work is supported by CIALL.

Powered by WPeMatico

Tadhail air Island Voices – Guthan nan Eilean

Le lasairdhubh

The fear that Gaelic is dying is nothing new. Folk have been warning that Gaelic could be dead ‘in ten years time’ since at least the 1980s, and folk have been agonizing about the imminent death of the language for much longer than that, but while not new, I would argue that this death discourse is self-sabotaging, potentially doing at least as much harm to our language revival movement as any active resistance from our enemies on the outside.

Successful language revivals are, first and foremost, vibrant social movements, but there is good evidence that in some cases this sort of negative discourse, often called ‘emergency framing’, can actually be less effective than more positive framing in motivating people to take action. This effect has not been empirically studied in Gaelic context yet, but if you think about it for a minute, it makes intuitive sense; for instance, it is reasonable to think that parents might be less likely to speak a language with their children, or enrol their children in a school that teaches in that language, if they think that that language is failing. Quite rightly, parents want to give their children the skills they will need to succeed in life, but the death discourse gives the opposite impression: that Gaelic is increasingly useless.

Or consider how politicians might interpret this discourse. As Gaelic activists, we are a very small group. Depending how you define ‘Gaelic activist’, there are a few dozen of us, or maybe a few hundred at most, so we don’t constitute a meaningful voting block by ourselves. To rally politicians to our cause, we have to convince them that our enthusiasm for Gaelic is shared by a significant percentage of the general public, but the death discourse, again, gives the opposite impression. From the perspective of politicians, it might appear politically naive, and possibly even undemocratic, to continue to dedicate public resources to a language that their own constituents appear to be abandoning.

Yes, Gaelic is a threatened language, and I am not arguing that we should lie to people, but I am arguing that we should tell a different story: a more hopeful and better balanced story, and thereby, a more accurate one. Any language revival is a mixture of good news and bad news, and while we have to be mindful of where we need to do more work, focussing almost exclusively on our fear that Gaelic will soon be dead actually misrepresents the situation. It may feel cool-headed, clear-eyed and realistic to some activists, but in reality, it is none of these things.

The problem with emergency framing in this respect is that it is both too optimistic and too pessimistic at the same time. It is too optimistic because it asserts that there is still a vernacular language left to ’save’, but as I have argued before, that horse bolted in the 1960s and 1970s, and there is no realistic prospect of reviving Gaelic as a universal vernacular language in the Islands or anywhere else in Scotland in either the short or medium term.

And emergency framing is too pessimistic because it asserts that Gaelic dying, when the truth is that by many measures, Gaelic has never been more popular in Scotland. There is exactly zero chance that Gaelic will die out as an everyday spoken language in the Islands, or in Scotland in general, in any of our lifetimes. Gaelic is changing—has changed—from a language spoken in territorial speech communities to one spoken in language networks, but it has not died. Engaged scholarship and effective advocacy alike should be about helping the Gaelic-speaking world to understand this change and to figure out how to make it work.

There is a persistent belief, though, shared by many Gaelic activists and even some scholars, that territorial speech communities are the sin qua non of living languages, but if we want to strengthen Gaelic as a vital, widely-spoken language into the 21st century, we have to work with Gaelic as it is in the real world, not as we wish it was. We have to work with those who are actually interested in learning, using and passing on the language, not force our revivalist aspirations on individuals or communities because we believe they should save their language.

In 1998-99, as part of his PhD research, Alasdair MacCaluim conducted a detailed survey of 643 learners and new speakers of Scottish Gaelic, and one of the questions he asked was, to what degree they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “Gaelic can only be saved if Gaelic speaking communities continue to exist in the Islands”. MacCaluim found that a clear majority of respondents, 67.6%, either agreed or strongly agreed. (p. 264)

And this is, I think, the heart of the problem. Many Gaelic speakers, including many learners and new speakers, need Gaelic to exist in the Islands as a common vernacular to satisfy their own understanding of Gaelic as a real, living language, but folk on the Islands were not put on this planet to serve as a means to someone else’s ends. They will make their own decisions, and the reality is that, to date, a significant proportion of Islanders have decided that they are not particularly interested in the Gaelic revival, at least for now.

There are, of course, plenty of folk living in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland who are passionate about Gaelic, who want to learn, use and pass it on, and they should be unstintingly supported, but there is also huge interest in learning and using Gaelic throughout Scotland, and if all these interested folk, wherever they may be, could be could be helped to become active Gaelic speakers, Gaelic’s future in Scotland could be really bright.

There is no limit to what we can achieve; we just have to fight together for the structures (and money) required to turn interest into ability and then into use, but to do this, to build the kind of vibrant, optimistic social movement that could successfully pressure the government to genuinely support the Gaelic revival, we first need to figure out how to tell a different story.

Post script: five things that are making me optimistic just now.

Cnoc Soilleir, South Uist – Cnoc Soilleir grew organically out of the Ceòlas movement in Uist, and it is an inspiration. Local grassroots activists created a cultural centre that should serve as an exemplary model for community-based language and cultural development.

Cultarlann, Inverness – Another amazing grass-roots-built Gaelic cultural centre, this one in Inverness.

Gaelic in Sleat – Several generations of (home-grown and incomer) Gaelic activists have built a level of institutional support for the language in Sleat that actually appears to be delivering a revival. The recent census results are very encouraging.

Gaelic numbers in Scotland – Some may talk these numbers down, and it is true that we don’t yet know who these new speakers are or what sort of Gaelic they can speak, but the fact that 12 thousand more people rated their own Gaelic abilities or those of their children highly enough that they were willing to record themselves or their children as Gaelic speakers is unquestionably significant positive news.

Ionad Gàidhlig Dhùn Èideann – Edinburgh Gaels are nothing if not persistent. It took Gaelic activists in the capital 13 years to win a Gaelic primary school, and they are still fighting the council for a Gaelic high school. It is taking them even longer to win the battle for a Gaelic centre in the city, but I wouldn’t bet against them.

“Gaelic could ’die’ in ten years.” The Scotsman, 7 December, 1983, p 7.

MacCaluim, Alasdair. (2002) Periphery of the periphery? Adult learners of Scottish Gaelic and reversal of language shift. PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh.

For a good review of the many questions and uncertainties around ‘emergency frames’ see: James Patterson, Carina Wyborn, Linda Westman, Marie Claire Brisbois, Manjana Milkoreit and Dhanasree Jayaram (2021) ‘The political effects of emergency frames in sustainability.’ Nature Sustainability 4, 841–850.

For an interesting recent article empirically showing this effect, see: Marjolaine Martel-Morin and Erick Lachapelle (2022) ‘Code red for humanity or time for broad collective action? Exploring the role of positive and negative messaging in (de)motivating climate action.’ Frontiers in Communication 7.

For a scholarly critique of the death discourse in the Scottish Gaelic context, see: MacEwan-Fujita, Emily (2006) “Gaelic Doomed as Speakers Die Out?: The Public Discourse of Gaelic Language Death in Scotland.” In Wilson McLeod (ed), Revitalising Gaelic in Scotland: Policy, Planning and Public Discourse. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press, 279-293.

And for a scholarly critique from a North-American perspective, see: Davis, Jenny. (2017) “Resisting rhetorics of language endangerment: Reclamation through Indigenous language survivance.”, Language Documentation and Description 14, 37-58. Thank you to Prof Martin Kohlberger for drawing my attention to this article.

Photo: Diego Delso, delso.photo, License CC-BY-SA

Powered by WPeMatico

Tadhail air Air Cuan Dubh Drilseach

Gàrraidhean Caisteal Chaladair / Cawdor Castle Gardens

Tha mi cho fortanach ‘s gum bi mi a’ tadhail air Caisteal Chaladair iomadh uair gach seusan turasachd, leis gun toir mi tursan-bus ann bho na loidhnearan ann an Inbhir Ghòrdain. ‘S dòcha gun sgrìobh mi mun chaisteal fhèin ann an eagran eile, ach am mìos seo tha mi airson na gàrraidhean aige a mholadh; tha mi an dòchas gum bi na dealbhan cuideachd a’ bruidhinn air an son fhèin.

Tha gàrraidhean eadar-dhealaichte ann, agus gach aon na thlachd dhuinn. Am fear as fheàrr leam fhìn, ‘s e sin Gàrradh nam Flùraichean, am fear as fhaisge air a’ chaisteal, air a dhìon le seann bhalla àrd, le geadagan is ceumannan dathach de gach seòrsa, preasan is craobhan fo bhlàth, oiseanan brèagha air cùl challaidean a lorgas tu gun dùil, agus an-còmhnaidh an caisteal fhèin mar dhealbh-chùil. Tha e làn obrach-snaidhidh nuaidh drùidhtich cuideachd, freagarrach dhan t-suidheachadh aca. Nuair a thèid thu a-mach tro dhòras sa bhalla chì thu an Gàrradh Fiadhaich, coille le craobhan sequoia fuamhaireil ri taobh na h-aibhne ach cuideachd làn rhododendron is azalea, bhrogan na cuthaige is blàthan creamha, agus cheumannan lùbach togarrach, àlainn fhèin aig an àm seo.

Air taobh eile a’ chaisteil tha Gàrradh Cuairtichte eile ann, an turas seo le cuairtean mòr ceàrnagach is ìomhaigh a’ Mhinotaur sa teis-mheadhan. Timcheall air tha seòrsa tunail de laburnum òir-bhuidhe am measg dhìtheanan fiadhaich, dìreach drùidhteach. Air a chùlaibh tha an Gàrradh-Pàrrais beag, le callaidean ìosal is geadagan-luibhean, agus ìomhaigh snaidhte de dh’Àdhamh is Eubha a’ fàgail Èden. Agus an uair sin feumaidh tu an t-slighe a lorg a-steach dhan Ghàrradh Gheal chruinn, is e air a chuairteachadh le callaid àrd mhòr is làn fhlùraichean is phreasan geala – agus le fuaran simplidh ealanta sa mheadhan. Agus mu dhèireadh thall chì thu an t-Ubhal-ghort, cuideachd le ceapach mòr rùbraib – agus craobh mheatailt iongantach le grian no gealach mhòr anns na geugan.

Tha e ri fhaicinn gu bheil Ban-Iarla Chaladair, Lady Angelika, glè mheasail is eòlach air gàrraidhean, is i ag obair còmhla ri sgioba beag ghàirnealairean sgileil gus am bi dathan is caochladh anns gach ràith, agus tha an caisteal fhèin làn rèiteachaidhean-fhlùraichean às a’ ghàrradh.

Agus na gabh dragh – tha beingean gu leòr ann, agus cupa math tì a’ feitheamh ort sa chafaidh!

++++++++++++++++++++++++++

I’m lucky enough to get to visit Cawdor Castle quite often each season as I take bus-tours there from the liners at Invergordon. I might write about the castle itself in another edition, but this month I wanted to recommend its gardens; and I hope the photos will also speak for themselves.

There are various gardens there, each one a delight. My favourite is the Flower Garden, the one nearest the castle, protected by a high old wall, with colourful flowerbeds and paths of all kinds, shrubs and trees in blossom, lovely corners you come upon unexpectedly behind hedges, and always the castle as backdrop. It’s also full of impressive, tasteful modern sculptures, appropriate to their surroundings. When you go through a door in the wall you see the Wild Garden, a woodland with giant sequoias by the river, and full of rhododendrons and azaleas, bluebells and wild garlic flowers, and inviting winding paths, just beautiful at this time of year.

On the other side of the castle there’s another Walled Garden, this time with a square maze, and a statue of the Minotaur in the centre. All around it there’s a kind of tunnel of golden laburnum among beds of wild flowers, just stunning. Behind it is the little Paradise Garden with low hedges and herb beds, and a small statue of Adam and Eve leaving Eden. Then you have to look for the way into the round White Garden, as it’s surrounded by huge high hedges, and is full of white flowers and shrubs – and has a simple but elegant fountain in the middle. And finally you’ll see the Orchard, which also has a large rhubarb bed, and an amazing metal tree with a big sun or moon in its branches.

It’s very evident that the Countess of Cawdor, Lady Angelika, is fond of gardens and very knowledgeable. She works with a small team of skilful gardeners so there’s colour and variety in every season, and the castle itself is also full of flower arrangements from the gardens.

But don’t worry – there are plenty of benches, and a nice cup of tea waiting for you in the cafe!

Further information: https://www.cawdorcastle.com/

Powered by WPeMatico

Tadhail air seaboardgàidhlig

Le Gordon Wells

Iochdar resident Lawrence Iain Alasdair ’ic Raghnaill (Lawrence MacEachen) recently entertained Tommy Macdonald in his home for a chat about his beautiful taigh-tughaidh (thatched house). At Island Voices we were privileged to be able to record their conversation, which we have now added to our “Taighean-tughaidh” playlist on YouTube.

As with the earlier recordings of Tommy and Betty, this conversation is presented in two alternative formats. Fluent speakers may choose simply to watch the whole thing in one go in the “omnibus” version, without any need for recourse to learning aids.

On the other hand, the full conversation has again been broken up into smaller parts, each of which is also supported by auto-translatable subtitles and a wordlinked transcript for the benefit of learners or non-speakers of Gaelic. Links to the transcripts are given in the YouTube video descriptions.

In Part 1, Tommy introduces us to Lawrence in his thatched house in Iochdar, South Uist, inherited from his aunt. Lawrence explains how it had been used as a byre for a time before he did it up again for his own use. It’s due for re-thatching again – in some respects a less arduous task than it used to be.

In Part 2, Tommy and Lawrence discuss the shaping of the roof and the corners of the traditional thatched houses to lessen the impact of the Hebridean gales, as well as the ease of use of local stone to build the thick walls. Lawrence has been told his is the only thatched house in the north of Scotland with a permanent resident, though others have been done up for holiday lets in accordance with sometimes strict planning regulations. There used to be many more of these houses in Iochdar.

In Part 3, Tommy and Laurence talk about some of the other thatched houses they remember, and discuss alternative thatching materials, including marram grass, heather, and rushes. Each has its own qualities, with different materials likely to be used in different areas. Care needs to be taken when gathering roofing materials.

These recordings have been enabled through the ongoing support of the UHI-led CIALL project.

Powered by WPeMatico

Tadhail air Island Voices – Guthan nan Eilean

Powered by WPeMatico

Tadhail air Ghetto na Gàidhlig – Bella Caledonia

Le Gordon Wells

“Fàilte oirbh gu fear eile de na còmhraidhean a tha seo, aig Comann Eachdraidh Sgìre a’ Bhac.”

Ishbell MacDonald (Ishbel Bhobshie), her brother Dòmhnall and John MacDonald (Swannie) chat with Coinneach Mòr.

Another wordlinked transcript has been created for this recording, with CIALL assistance:

Powered by WPeMatico

Tadhail air Island Voices – Guthan nan Eilean

Le Gordon Wells

Select any video clip in this landscape format, or use the phone-friendly portrait layout.

Select any video clip in this landscape format, or use the phone-friendly portrait layout.

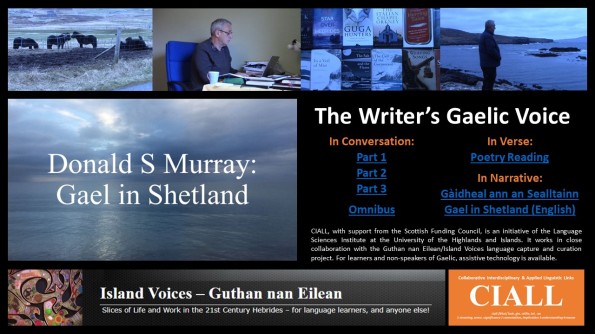

Lewis-man Donald S Murray is a Shetland resident. As an established writer, mostly in English, how does he keep his Gaelic going while living away from the Ness community where he acquired it?

Following on from our recent “Jamaican in Wales” feature, that’s a key question underlying this second small collection of videos in our Island Voices extension series looking at language use in an “exile” context. Again, we have added poetic recitation to the standard documentary plus interviews format in our Language Capture and Curation model, with the narrative documentary also being reduplicated in English. All films in the collection can be accessed through the above poster in either landscape or phone-friendly portrait layout.

As Donald freely acknowledges, he mostly uses his Gaelic for talking rather than writing, and we’ve duly given greater weight in this package to his conversational voice, though we’re pleased to also platform some of his less well-known Gaelic poetry. While he obviously has many Gaelic speakers in his ever-widening readership, there will also be many non-speakers of Gaelic who, up until now, will only know his “voice” through the written English page. Here he speaks openly and frankly in what he accounts his native language, establishing direct unfiltered contact with his home community in Lewis. At the same time, YouTube subtitling allows others to read his words as he speaks, with the on-off choice of auto-translation into a wide range of other languages, English among them. (Click the Settings Wheel to view the full range and select your own preference.)

The conversation component has additionally been split into three parts, for the benefit of learners or non-speakers of Gaelic, each equipped with optional closed caption subtitles. The “omnibus” edition is intended for those with no need for such assistance.

In Part 1 Donald talks about his family background and upbringing, first in East Kilbride and then in Ness, Isle of Lewis. He also talks about community and school influences and how they affected his acquisition of Gaelic. A spell of work and then university studies followed on the mainland, before he returned to the Western Isles to teach, first in Lewis, and then Benbecula. He also refers to challenges he had to overcome during these stages of his life.

In Part 2 Donald talks about life as a Gaelic speaker in Shetland, noting how he maintains his speaking skills through long-distance conversations and frequent radio interviews. He points out the relative infrequency of his writing in the language as a common feature amongst fluent Gaelic speakers who normally practise their literacy through English, so his writing about his home community is often a process of translation from Gaelic in his head to English on the page. He regrets the lack of theatre-based literary work in the Western Isles, and highlights the value of the short story format in an island community setting. One advantage of now living away from Lewis is the greater freedom he now feels to express critical opinion freely.

In Part 3 Donald talks in some detail about the difficulties he encountered in first writing his novel, As the Women Lay Dreaming, and then in talking about it afterwards, often in relation to dealing with varying experiences of trauma at personal as well as community levels. The theme returns in a very different community context in The Salt and the Flame, exploring urban American tensions through Gaelic emigrant eyes. He is thankful for his father’s encouragement of his wide reading interests as a young boy in Ness, which are reflected in the book alongside the wider research he conducted as part of the writing process.

Powered by WPeMatico

Tadhail air Island Voices – Guthan nan Eilean

Le Gordon Wells

Um pequeno documentário em Português sobre um encontro do Parlamento de Crianças de Uist e da Barra

Um pequeno documentário em Português sobre um encontro do Parlamento de Crianças de Uist e da Barra

At Island Voices we welcome participation and contributions from speakers, learners, and researchers of any age and stage in multiple languages from all over the globe!

Marina Yazbek Dias Peres is a student in the Research Program at Princeton High School, New Jersey, in the USA. In this program, each student learns to research, and conducts their own project over the course of three years. Marina’s research project is focused on “uncovering the motivation behind the preservation of dying/endangered languages, and analyzing the causation behind the lack of their use”.

Marina is bilingual in English and Portuguese, and is also studying French and Mandarin in school. During discussion of her research topic with Gordon Wells she kindly offered to add Portuguese to the Island Voices list of “Other Tongues“, choosing the Children’s Parliament in Benbecula film in Series 2 Generations. We were happy to accept! Perhaps her example will inspire others like her to take an interest and think about participating too?

A wordlinked transcript with the video embedded is available here: https://multidict.net/cs/11930

Powered by WPeMatico

Tadhail air Island Voices – Guthan nan Eilean